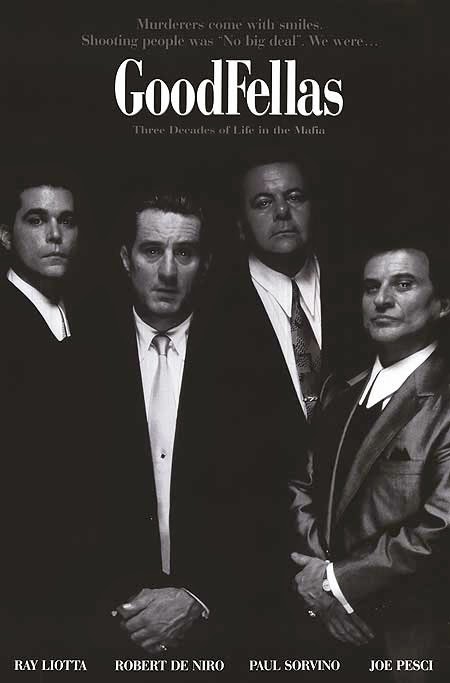

Martin

Scorsese’s sprawling 1990 crime film adaptation of the novel “Wiseguy” by Nicholas

Pileggi begins with perhaps the most understated of the film openings I have

chosen to blog about. It is restrained but also horrific in its execution that not

only introduces audiences to the character of Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), but

introduces them to the shockingly realised portrayal of organised crime that

both Hill and Scorsese are enamoured with.

What

is perhaps most striking about this opening scene is its selective use of score

and music. Scorsese deliberately chooses to open the film without orchestral

music, or even play the famous Rags to Riches earlier; a wise move that would

otherwise disrupt the quiet and tense atmosphere of the scene in question. The

absence of music until the very end of the scene creates greater realism, and

speculation about where the scene will be going. The music appears over a zoom-in

and freeze on Hill, for the reason that the words “rags to riches” themselves

encapsulate the entire motivations behind Hill turning towards a life of

organised crime; that he, like many other Americans who believe in the “American

Dream”, wants to achieve success in their lifetime. Scorsese uses this to directly

contrast Hill’s own dreams as a gangster, and encapsulates the film as a

deconstruction of the commonly used story.

Scorsese’s

purposeful use of sound is chosen

to combine realism with tension. The scene relies exclusively on

diegetic sound and dialogue, using the steady noise of Hill’s Pontiac on the

road to the crickets heard outside in the dark. Despite these sounds creating

the illusion of normalcy, we are still led to understand that something out of

the ordinary is happening. Tommy’s (Joe Pesci) knife as he is stabbing Billy Batts

in the back of the car elicit shock and extreme unease. The following gunshots

are loud and deafening compared with the background noise, and Scorsese places

an insert of Hill flinching to show us there is at least a small segment of humanity

in him. This subtly draws attention to the fact that Hill does not attack Batts’s

body like Robert DeNiro and Pesci’s characters do.

When a film features a scene set after daylight hours, obvious forms of lighting may

break the viewer’s suspension of disbelief. Scorsese uses this setting to his

advantage by devising alternative forms of lighting within the setting.

Specifically, these come only from the lights of Hill’s car. By using the back

lights of the Pontiac to cast a glare upon the three main characters outside, this

creates an unsettling aura that bathes them in red. Symbolically, it illustrates

right away that they are not the good guys. Where this film is similar to Trainspotting is that both

begin in a rearranged order; scenes that actually occur about midway through

the story occur first in the film to both engross and cause audiences to

speculate (this sentence has been rearranged as well by the way).

REFERENCES:

Goodfellas. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Warner Bros., 1990. Film.

Corrigan, Timothy & Patricia White. The Film Experience: An Introduction.

Third Edition. New York: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2012. 471, 473, 474, 482. Print.

https://www.movieposter.com/posters/archive/main/44/MPW-22061

http://www.weirdworm.com/media/img/stories/9-of-the-coolest-movie-intros/goodfellas.jpg

http://www.weirdworm.com/media/img/stories/9-of-the-coolest-movie-intros/goodfellas.jpg

No comments:

Post a Comment