The 1929 surrealist short film Un Chien Andalou, directed

by Luis Bunuel, has one of the strangest and yet most visually striking of

opening sequences in film.

The main goal of Bunuel’s film is not to tell a believable

story or straightforward narrative, rather the intention to shock audiences

with its juxtaposition of images, disjunctive editing style and use of

mise-en-scene. Through this, Bunuel uses disconnected images and connects them

through shock cuts in order to present the resulting visual horror to the

audience. A cut from the man with the razor on the balcony to the night sky

shows a thin line of cloud moving towards the circular moon, therefore

connecting to the infamous eye cutting scene. Another example of disjunctive editing is the

famous image of the man with the razor holding open a woman’s eye as if

preparing to slice it open, which then cuts to a dead calf’s eye being cut instead.

Anyone that goes back and rewatches it (God forbid) will

find that these are two completely different shots, but the overall action

remains the same. The shock cut between the night sky and the cutting of the

eye also shows two completely different shots, but convey the same action on

screen. Bunuel creates symbolism between each two shots, but a viewer would

know that regular weather patterns have no real connection to a motivation behind

wanting to inflict grievous harm upon a person. Therefore, the goal of

surrealism is to create a world that has qualities of but also does not exist

in real life.

While the three other films talked about all have openings

that occur later in the narrative and thus require explanation as a result,

Bunuel’s opening is constructed without an explanation for what is seen on

screen, as it functions as a prologue completely unconnected to the rest of the

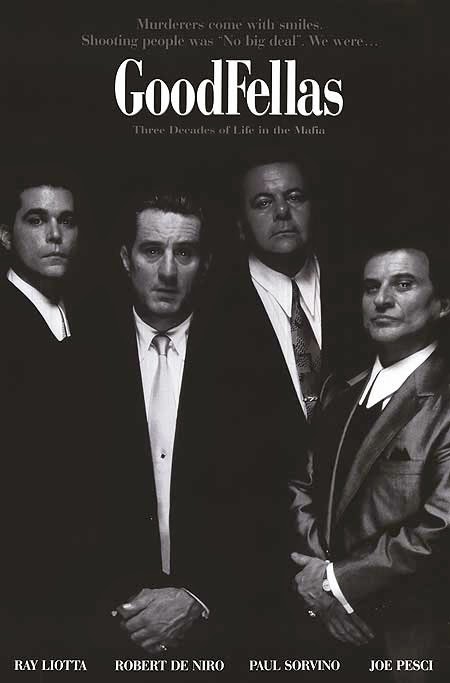

film. In Goodfellas, violence is used to accurately portray mob dealings as

close as it can, where in Bunuel’s film it serves no real purpose outside of

startling imagery. Fight Club and Trainspotting’s openings are a culmination of

events preceding it but told out of order, and violence is implied from the

mise-en-scene of a gun in the narrator’s mouth in the former, and running from

the authorities in the latter, while Bunuel’s film does not imply any violence.

REFERENCES:

“Luis Bunuel: Un Chien andalou (1928).” July

19th 2013. YouTube. Web video.

Accessed 27th April 2015.

Corrigan, Timothy & Patricia White. The Film Experience: An Introduction.

Third Edition. New York: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2012. 471, 479, 480. Print.

http://www.heyuguys.com/images/2014/08/Un-chien-andalou.jpg